History of Japanese Market

via Nikkei 225

Looking back at 70 years history of the Tokyo market since 1950 through the Nikkei 225.

Looking back at 70 years history of the Tokyo market since 1950 through the Nikkei 225.

On March 4, 1953, there was a breaking news saying that Stalin, Premier of the Soviet Union, was in critical condition. The following day, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun reported that Stalin was in critical condition based on a broadcast from Moscow. The report included speculation that he had already died and that there would be extraordinary reactions by many countries. The news prompted investors to sell off leading stocks and munitions-related stocks in Tokyo. This triggered the first full-scale stock market crash since the reopening of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in May 1949.

The Nihon Keizai Shimbun reported that the market in Tokyo on March 5 was almost in a depression, with the mainstay Tokio Marine down 113 yen, Heiwa Real Estate down 57 yen and Shin Mitsubishi Heavy Industries down 63 yen. The Nikkei Stock Average (then the Tokyo Stock Exchange Adjusted Average) was down 37.81 yen to 340.41 yen. A drop of 37 yen is a small move as for today, but at the time of December 1952, the level of the market was known as the “one-dollar market” since the Nikkei average surpassed 360 yen, which was same as the yen-dollar exchange rate. Consequently, the rate of decline reached exactly 10%, which is still the 4th largest in the history of the Nikkei 225.

After that, the Nikkei 225 continued to fall, declining to below 300 yen to 295.18 yen on April 1. Compared to the high of 474.43 yen on February 4, almost two months earlier, the index was sharply down 37.7%. The reason for this crash was the end of the stock market boom that began in 1950 as the Korean War started.

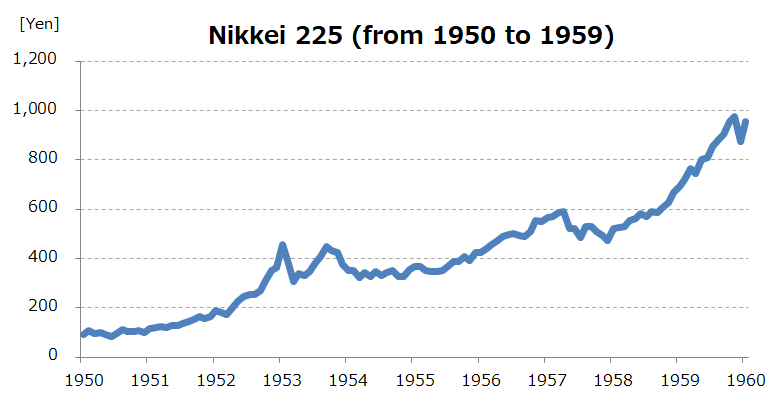

The Korean War, which started in June 1950, was an opportunity to restore the soundness of the Japanese economy, which was destroyed by World War II. The so-called special procurement of materials for the United Nations military in the Far East and the export boom, driven by purchases of weapons by many countries, revitalized the Japanese economy and sparked a powerful stock market rally.

At the beginning of July 1950, the Nikkei 225 dropped to 85.25 yen, the lowest level since the reopening of the exchange, due to an economic downturn caused by the Dodge Line. However, this was followed by a prolonged boom that lasted more than two years. The Nikkei 225 recovered to the 100 yen level at the end of 1950 and rose to 170 yen in October 1951, within reach of its previous high of 176.89 yen (September 1, 1949). The following year, the index rose to the 200 yen level in April and the 300 yen level in October. In December, the index reached the dollar exchange rate of 360 yen. In 1953, the stock market heated up even more, with the Nikkei 225 surpassing 400 yen and reaching 474.43 yen on February 4. Compared to the lowest point in July 1950, the Nikkei 225 rose 5.6 times in two and a half years.

But Japan’s real economy was already in an adjustment phase. The momentum for an armistice began to increase following peace talks in July 1951 and the special procurement stopped. By 1952, companies in many industries began to downsize their operations because there was excessive production capacity. Nevertheless, the stock market continued to rise for a little over a year after the economy entered an adjustment phase.

Then came the Stalin Shock. This marked the end of the first post-war stock market boom that drew the public to stock investments. The impact of the Stalin Shock was significant because the stock market had gone too far from the real economy. Against the backdrop of the balance of payments deficit, monetary tightening measures started in October 1953 and the stock market entered a period of weakness following the prior phase of strength.

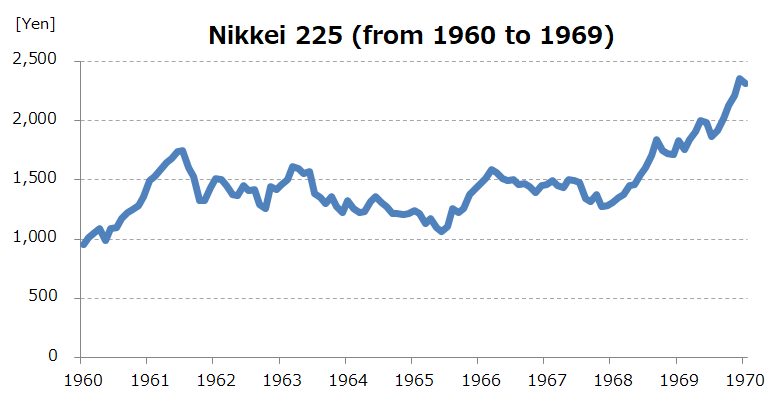

May 28, 1965, became an important day in Japan’s post-war economic history because the Bank of Japan decided to extend special loans to securities companies. The loans were virtually unsecured and unlimited. First, Yamaichi Securities, a major securities company, received a loan. Two months later, in July, a special loan was extended to Oi Securities as well. This unusual measure prevented the spread of credit uncertainty. However, the process leading up to these special loans was quite dramatic.

The 1965 recession, symbolized by the bankruptcies of Sun Wave and Sanyo Special Steel, was a relatively short in terms of the real economy. But for the securities industry, the recession was the final stage of a long-term slump in the securities market. Securities companies had been trying to expand their business without building a sound base for operations. As a result, these companies had weak management infrastructures. In January 1964, Japan Kyodo Securities Co., Ltd. was established as a neutral organization to support stock purchases. A battle started with the goal of keeping the Nikkei 225 above 1,200 yen but eventually failed, resulting in the 1965 recession.

One of the reasons Yamaichi Securities' problems attracted attention was the sudden resignation of its top management after the company posted a large loss in its fiscal year ended September 1964. As the industrial recession worsened, Yamaichi received even more attention amid accurate media reports about the company’s problems.

In May 1965, the Ministry of Finance asked Tokyo-based newspapers to refrain from covering the Yamaichi problem until a restructuring plan was finalized. However, the May 21 morning edition of a newspaper that had not been asked to refrain from this coverage had articles about the Yamaichi problem. All other newspapers then began coverage of the predicament of Yamaichi's management and its restructuring plan in the evening editions of the same day. The Nihon Keizai Shimbun wrote, "Yamaichi Securities finalizes restructuring plan, putting lending rate on the shelf".

At a special press conference on the same day, Finance Minister Kakuei Tanaka stressed that individual investors will not be inconvenienced by this problem. A Finance Ministry official said that the measures to restructure the securities industry have passed the test. The ministry was desperately trying to stop the spread of the credit crisis. However, the newspaper reports led to a surge at Yamaichi in withdrawals of financial bonds under management and cancellations of investment trusts. It was similar to a bank run. The stock market was filled with anxiety.

The Nikkei 225, which started at 1,227 yen in 1965, hit a low of 1,115 yen on April 3 but fell below this level on May 26 and briefly dropped below 1,110 yen. On May 28, this index fell below 1,100 yen. Yamaichi and other securities companies were affected by these increasing withdrawals. Due to this situation, the major securities companies were too busy with serving their own customers to deal with the market’s problems.

On May 28, one week after the Yamaichi newspaper report, the decision was made to extend unsecured and unlimited loans under Article 25 of the Bank of Japan Act. The announcement stated that "the government and the Bank of Japan have decided that the Bank of Japan will provide the funds needed by the securities industry at this stage through major banks. Three major banks will provide these loans to Yamaichi. We will quickly use decisive measures for securities financing, including special financing measures."

The Bank of Japan's special loan was intended to target the entire securities industry rather than only a few companies in order to maintain credit discipline. The fact that the loans ended up being limited to just two companies, Yamaichi and Oi, shows that the BOJ's special loan policy was appropriate. The securities market subsequently recovered with the support of the government’s decision to issue bonds to overcome a recession for the first time in the post-war era. The health of the securities industry was restored as Japan’s economy grew rapidly.

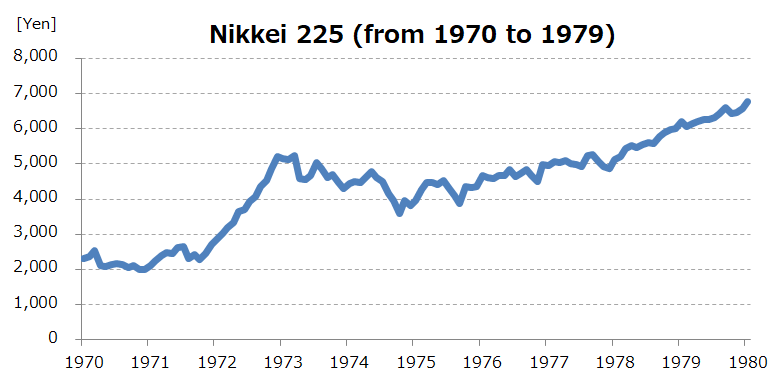

On August 16, 1971, President Nixon's announcement of measures to strengthen defensive measures for the dollar, including the suspension of the exchange of dollars for gold, upset the Japanese stock market so much that the Nikkei 225 plunged 215 yen, a drop of 7.68%. This decline set a new record by surpassing the so-called Stalin plunge. The decline was 7.68%, but the margin of decline exceeded the Stalin plunge and was the largest ever recorded at that time. This was the so-called Nixon shock. The upheaval continued, with the Nikkei 225 down 550 yen in the four days to August 19. The shock to the stock market was significant because the Nikkei 225 had been high and market sentiment was bullish until the first half of August, immediately prior to the shock.

With the end of the dollar's gold backing, the long post-war International Monetary Fund system collapsed and the era of the 360-yen dollar exchange rate ended. After this, the yen entered revaluation period. However, the Nixon administration's trade balance improvement measures and the appreciation of the yen did not diminish the competitiveness of the Japanese economy. In hindsight, the appreciation of the yen was merely a correction to reflect the Japanese economy's strength.

Japan’s trade surplus in 1971 surged to $7,787 million, almost double the previous year's surplus, and in 1972 further increased to $8,971 million. Foreign exchange reserves increased from $15.2 billion at the end of 1971 to $18.3 billion at the end of 1972.

At this time, earnings of Japanese companies were declining and capital expenditures were sluggish. Although the trade surplus and rising foreign exchange reserves raised the volume of yen-denominated funds, very little was used for capital expenditures. Idle funds were used to buy land and stocks. Companies used their own money as well as bank loans for speculation.

As a result, the Nikkei average, which was around 2,700 yen at the end of December 1971, rose to 5,200 yen at the end of December 1972. On January 24, 1973, the average reached the peak of this surplus liquidity market at 5,359 yen, an increase of almost 100% in one year. The speculative fever of this period extended not only to land and stocks, but also to golf memberships, precious metals and lotteries.

However, another upward revaluation of the yen and the collapse of the fixed exchange rate system in February 1973 ended the excess liquidity market. Furthermore, rising prices, especially for primary commodities, became more pronounced, leading to the oil shock of the fall of 1973.

In the fall of 1973, when the oil crisis started, the Nikkei 225 was declining after the prior year’s strength. At the end of October, the average was down more than 1,000 yen from its January high. In addition, the Nikkei 225 dropped to 3,355 yen in the fall of 1974. Subsequently, the stock market recovered, but it was not until 1978 that the Nikkei 225 exceeded the January 1973 high, which demonstrates the magnitude of the 1973 peak.

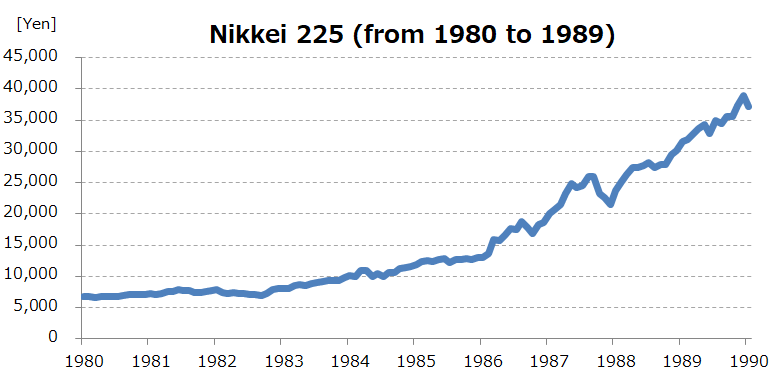

On Monday, October 19, 1987, a stock market slump, triggered by the crash of stock prices in the United States, quickly occurred around the world. On Tuesday, October 20, the Nikkei 225 plunged 3,836 yen, or 14.9%. The closing price on that day was 21,910 yen. This was the largest single-day drop ever and the first time in 34 years that the Stalin plunge of March 5, 1953 (down by 10.0%) was surpassed. This is still the biggest single-day decline in terms of both the size and percentage of the downturn.

However, the decline of the Dow Jones Industrial Average on October 19 was 23%, so the Tokyo market’s drop was modest in comparison. Furthermore, the subsequent recovery process in Tokyo was different. In 1988, the Nikkei 225 began to recover significantly. The average, which was at 21,000 yen at the beginning of the year, rose rapidly and three months later, at the beginning of April, exceeded the pre-crash high of 26,646 yen. Stock prices in Japan remained strong after that, enabling Japan alone to continue to post rising prices while markets in Europe and the United States were lackluster.

Although the rally in Japan was triggered by more accounting flexibility for institutional investors, which is a technical factor, the explanations given after the rally started were very positive. "Japan is shifting from an export-dependent to a domestic demand-driven economy," "Every aspect of the economy is benefiting from the strong yen." "The Japanese economy is in excellent shape.” As the confidence of investors and market participants increased, the Nikkei 225 continued to climb. However, the bubble economy was already emerging.

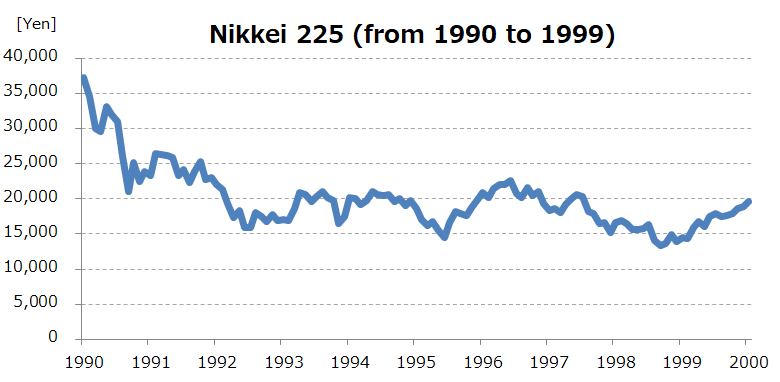

In 1989, the last year of the Showa era, the stock market was relatively quiet early in the year because of the somber mood due to the death of the Emperor. The Nikkei 225 stayed at the 30,000 to 31,000 yen level between January and March. Stock prices then gained momentum around the start of the new fiscal year in April, and the Nikkei 225 moved up about 1,000 yen every month. In the last months of the year, prices moved up even faster and ended 1989 at a record high 38,915 yen. After surpassing 30,000 yen for the first time in December 1988, the average shot up nearly 8,800 yen in only one year. Many people were very optimistic about 1990, even saying that a Nikkei average of 50,000 yen was possible.

The bursting of the bubble economy and the severity of its damage became clearly evident in 1991-92. A search of the four Nihon Keizai newspapers (the Nikkei and the three specialty newspapers) revealed that the number of articles in with the words "bubble" or "collapse" was only 49 in 1990. But this number jumped to 888 in 1991 and increased to 1,079 in 1992. Overall, there were many more articles with a negative tone.

In 1991, the Nikkei 225 started in the 24,000 yen range, then moved back and forth while weakening until it ended the year at 23,000 yen. In 1992, however, the average fell below the 20,000 yen level in March to almost half of its 1989 high. Next, the average plunged to the 14,000 yen level in August 1992. From a macroeconomic standpoint, the economy started to recovery in the fall of 1993. However, the recovery lacked vitality and the atmosphere of a recession persisted for a long time. The stock market slump at that time may have been caused by expectations for a period of lackluster economic performance in Japan.

In 1995, when the yen reached a high of 79.75 yen to the dollar, and in 1997, when Yamaichi Securities shut down voluntarily and other financial institutions went bankrupt, the Nikkei 225 did not go below the 14,000 yen level. However, the economic recovery, which had been tenuous, was crushed by hasty fiscal reconstruction measures such as raising the consumption tax rate and social insurance premiums. In October 1998, when the credit crunch and financial system instability peaked, the Nikkei 225 fell to 12,879 yen, its lowest point since the bursting of the bubble. The massive infusion of public funds into major banks finally ended the risk of a stock market free-fall.

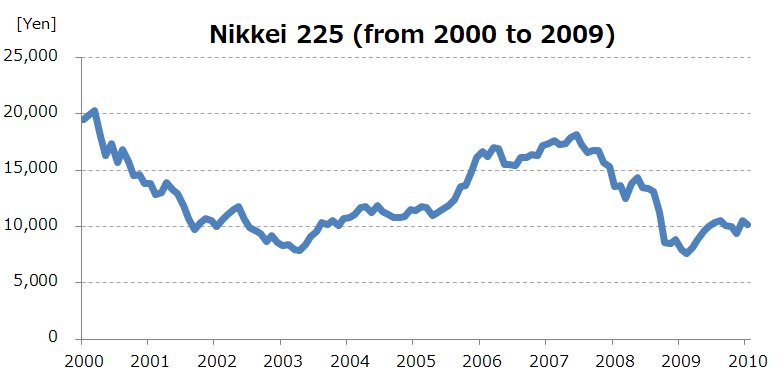

In the 2000s, the Japanese stock market was at the mercy of international economic turbulence. On March 10, 2000, the Nasdaq Composite Index, which includes many information technology stocks, briefly reached 5,132.52, more than twice the level of only one year earlier. This was the peak of the popularity of Internet-related stocks, known as the "dot-com bubble." The bursting of the IT bubble spread to Japan as well. The Nikkei 225 index, which had been above 20,000 yen in March 2000, fell below 15,000 yen in October 2000 and fell to 10,713 yen at the end of August 2001, very close to breaking through 10,000 yen.

Next, the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the U.S. slammed stock prices. On September 12, the Nikkei 225 dropped below 10,000 yen and closed at 9,610 yen, 682 yen (6.6%) lower than the previous day. Stock prices recovered, but in the middle of 2002, the index again started moving down faster because of fears of a worsening U.S. economy. The average fell below the post-911 low and then below 9,000 yen in October. In the first half of March 2003, the Nikkei 225 dropped below 8,000 yen for the first time in 20 years, partly due to tension involving the approaching U.S. war with Iraq.

After this downturn, the Nikkei 225 moved up for four years until the subprime mortgage crisis started in the U.S. in 2007. This four-year period was the biggest recovery for the stock market since the bursting of the bubble. Stock prices were supported by 73 months of economic expansion, the longest in the post-war period, that ended in February 2008.

This economic boom benefited greatly from U.S. monetary easing and the U.S. housing boom. However, the side effects of these measures came to the surface in the form of the subprime loan crisis. The Nikkei 225 was at the 18,000 level in July 2007, but plummeted to the 15,000 level in August as U.S. stocks fell and the yen strengthened against the dollar due to the subprime loan problem. After that, stock prices in Japan continued to decrease bit by bit because of the concerns about the impact of the subprime mortgage crisis on the U.S. economy. In September 2008, when Lehman Brothers was forced into bankruptcy, the world's financial markets fell into turmoil.

After the “Lehman shock,” the Nikkei 225 fell to a post-bubble low of 7,100 yen in October. On March 10, 2009, as investors’ concerns increased due to General Motors’ problems and other events, the Nikkei 225 closed at 7,054.98 yen, almost falling below 7,000 yen. The Nikkei 225 had not been this low for 26 years.

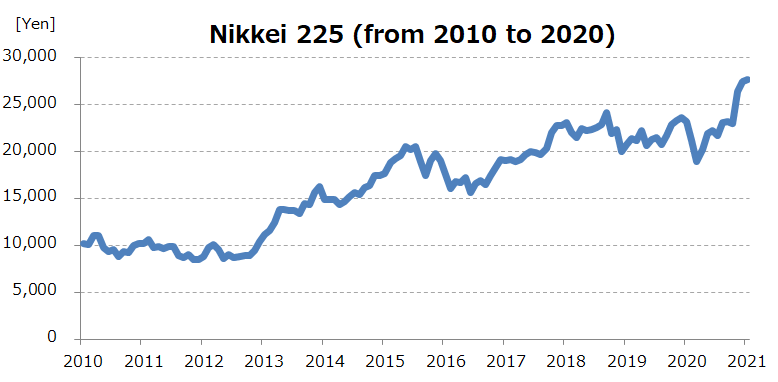

In 2010, the Nikkei 225 initially stayed around 10,000 yen. But stock prices were impacted in 2011 by the Great East Japan Earthquake that happened on March 11. As the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant became increasingly serious, the Nikkei Stock Average dropped 1,015 yen to close at 8,605 yen on March 15. This 10.55% decline was the third largest after Black Monday of 1987 and the Lehman Shock of 2008.

The second Abe Shinzo cabinet started at the end of 2012. To end deflation, the Japanese government unveiled Abenomics, a combination of three arrows: bold monetary easing, a flexible fiscal policy, and a growth strategy to stimulate private sector investment. Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who took office in March 2013, launched a bold monetary easing program, including large-scale purchases of long-term government bonds, with the goal of a 2% annual inflation rate. Foreign investors stepped up their purchases of Japanese stocks in response to policies of the government and Bank of Japan. The weakening of the yen provided a tailwind, and the Nikkei 225 recovered to the 15,000 level in May.

In 2014 and 2015, the depreciation of the yen and falling oil prices led to a recovery in the performance of Japanese companies. The Nikkei 225 recovered to the 20,000 yen level for the first time in 15 years on April 22, 2015 on a closing basis. However, in July, the Shanghai Composite Index in China, which had been driving the growth of the world economy, plummeted and the Nikkei 225 fell below 20,000 yen again.

In 2016, the Nikkei 225 was extremely volatile because of unexpected events, such as the result of the June Brexit referendum. At one point the index fell below 15,000 yen. The tide turned in November when the U.S. presidential election was held. The Nikkei 225 staged a powerful rally as the dollar strengthened and the yen weakened in response to Donald Trump’s victory. In 2017, the Nikkei 225 index moved back and forth under the 20,000-yen level due to the North Korean missile launches and other reasons. But in October, when the ruling party won the House of Representatives election in Japan, the index increased for 16 consecutive business days for the first time in its history. The 2017 year-end close was almost 20% higher than at the end of 2016 and the highest since 1991.

Historical Data

displays daily, monthly and annual values of Nikkei 225 since its inception

Current Components

shows the most recent constituents of Nikkei 225

New & Release

summarizes the news and releases published by Nikkei with screening function

Daily Summary

overviews the Tokyo market condition on a specific day in the past via Nikkei 225